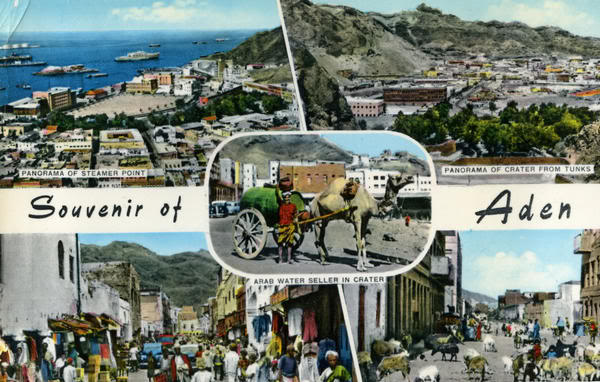

I lived in Aden as a child in the 1960s. I have very fond memories of the place and a clear understanding of how and why we, the Brits, came to be there, and how and why we left. History is full of little ironies, and Aden highlights several.

The first irony is why we were in Aden in the first place. One of the main reasons we went there over 170 years ago, was to combat piracy from Somalia and from along the southern tip of Arabia. It was seriously disrupting global shipping trade passing up the east coast of Africa and across to India. As most of that trade was ours, it was our job to deal with it. We dealt with it by established a naval base at Aden from which to patrol the Gulf of Aden and suppress piracy from Somalia, and by afterwards signing peace treaties with the various sheiks and sultans along the coast. They agreed not to allow piracy from their territories, and we agreed not to invade them. They became known collectively as the Trucial States. It’s a sign of the times that it now falls to the American and Chinese navies, amongst many others, to deal with modern-day Somali piracy.

The second irony is that having once kicked us out, Yemen has applied to join the Commonwealth. Aden in particular wants to break away from Yemen, which it became part of after independence, and has a specific goal of joining the Commonwealth. Yemen as a whole has already applied for membership so it’s not a contentious issue there. Similarly, Somaliland, a British Protectorate until 1960, wants to break away from Somalia, which it became part of after independence, and it too wants to join the Commonwealth. As much as I am a fan of the Commonwealth, I don’t see it as a “magic bullet” solution for failing states. Being a member of the Commonwealth hasn’t ensured that Pakistan, for example, has been able to deal with its own troubles in the North West Provinces. If anything, it has been a conduit that has eased the spread of al Qaeda to the UK, a route they have already started using from Yemen.

Third, the reason Yemenis wanted us out was to assert Arab nationalism, encouraged by Gamal Abdel Nasser who was in turn supported by the Soviet Union with money, weapons and ideology. Neither of them are around any more, but there is a more virulent and dangerous threat now in the form of al Qaeda, who have established a large base of operations in Yemen and thrust Aden back into the news headlines. Bin Laden has a more radical and dangerous agenda than Nasser ever had and, since the Cold War has ended and we have dropped our guard, he doesn’t need the resources of a superpower to back him up. Our own resources, such as the Internet and ease of travel, serve him well enough.

Fourth, the circumstances of our withdrawal from Aden have been, and may be, repeated in Iraq and Afghanistan. We were fighting a rear-guard action against two rival factions vying with each other for domination after we were gone – they had to be seen to be kicking us out. As well as fighting amongst themselves, they continued attacks on British troops even after we had begun to pull out. Bringing the warring Sunni and Shiite factions together has been the biggest challenge for the post-Saddam regime in Iraq. Afghanistan may be a different story unless the warlords can combine to challenge the Taliban.

Fifth, we had the support of Adenis loyal to the local sultans and they suffered vicious retribution afterwards. That pattern may well be repeated in Afghanistan, making anyone – police, army, civilian workers – associated with Hamid Karzai or the UN or Nato likely targets for the Taliban. In Aden, they remained loyal to their sultans and on our side until the end, will that be the case in Afghanistan?

Sixth, while we allowed the sultans to run their own areas outside the port of Aden itself, they were corrupt, autocratic and incompetent. It was as much to get rid of them that the insurgents, as they would now be called, were fighting. That is certainly true in Afghanistan today.

Seventh, the other reason we were in Aden was to establish it as coaling station to service the Royal Navy and our vast merchant fleet. In the post World War Two trade boom, Aden became the second busiest shipping port in the world and in 1958 only New York had more ships per day. But coincident with us pulling out Nasser closed the Suez Canal in 1967 following the Six Day war with Israel, and at a stroke wiped out Aden’s economy. It remained closed until 1975 and pushed South Yemen, as it had become, even further into the hands of the extremists. Afghan villagers have one cash crop – opium. We can’t just wipe that out, we need to ensure they have a viable alternative economy or the effect will be the same, to force them to support their own extremists, the Taliban.

We should try to learn from our experiences, positive and negative, in Aden (1960s), Iraq (1920/30s) and Afghanistan (1840s, 1870s, and again in 1919), as well as in other parts of the world where we have had to deal with insurgencies. Malaya (The Emergency), Kenya (the Mau Mau), and Palestine (Irgun, the Stern Gang) are just three more recent examples of many. We’ve got it right in some places, and dreadfully wrong in others.

History repeats itself because the people and the issues are always the same.